1 + 100[1] 101The most basic way to interact with R is to type code directly in the console

- type expression to evaluate

- hit return

- output of the evaluation of the expression is printed to the console below

The simplest thing you could do with R is do arithmetic.

1 + 100[1] 101If you type in an incomplete command, R will wait for you to complete it:

+Any time you hit return and the R session shows a + instead of a >, it means it’s waiting for you to complete the command. If you want to cancel a command you can hit Esc and the console will return to the > prompt.

To make code and workflows reproducible and easy to re-run, it’s better to save code in a script and use the script editor to edit it. This way, there is a complete record of your analysis.

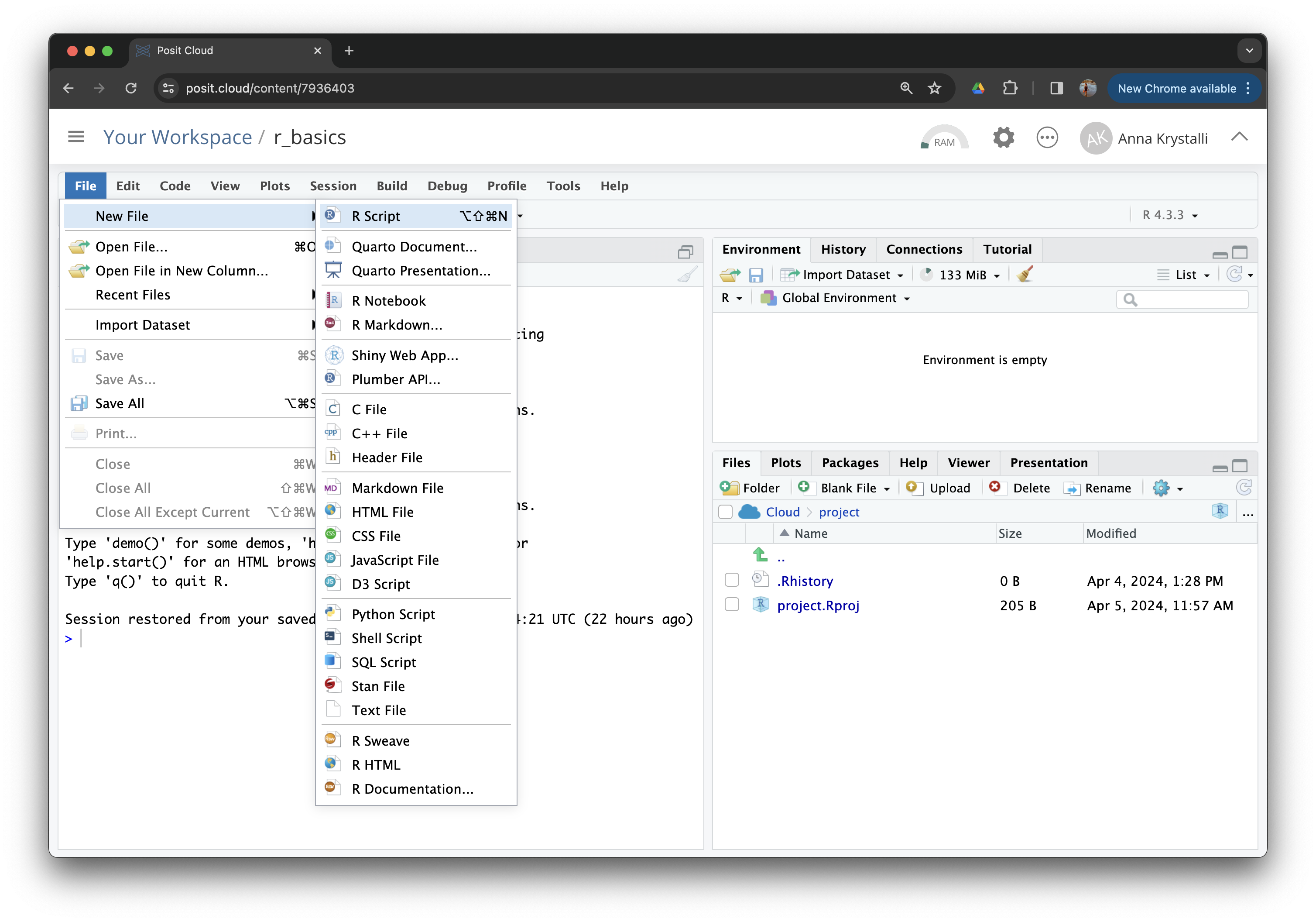

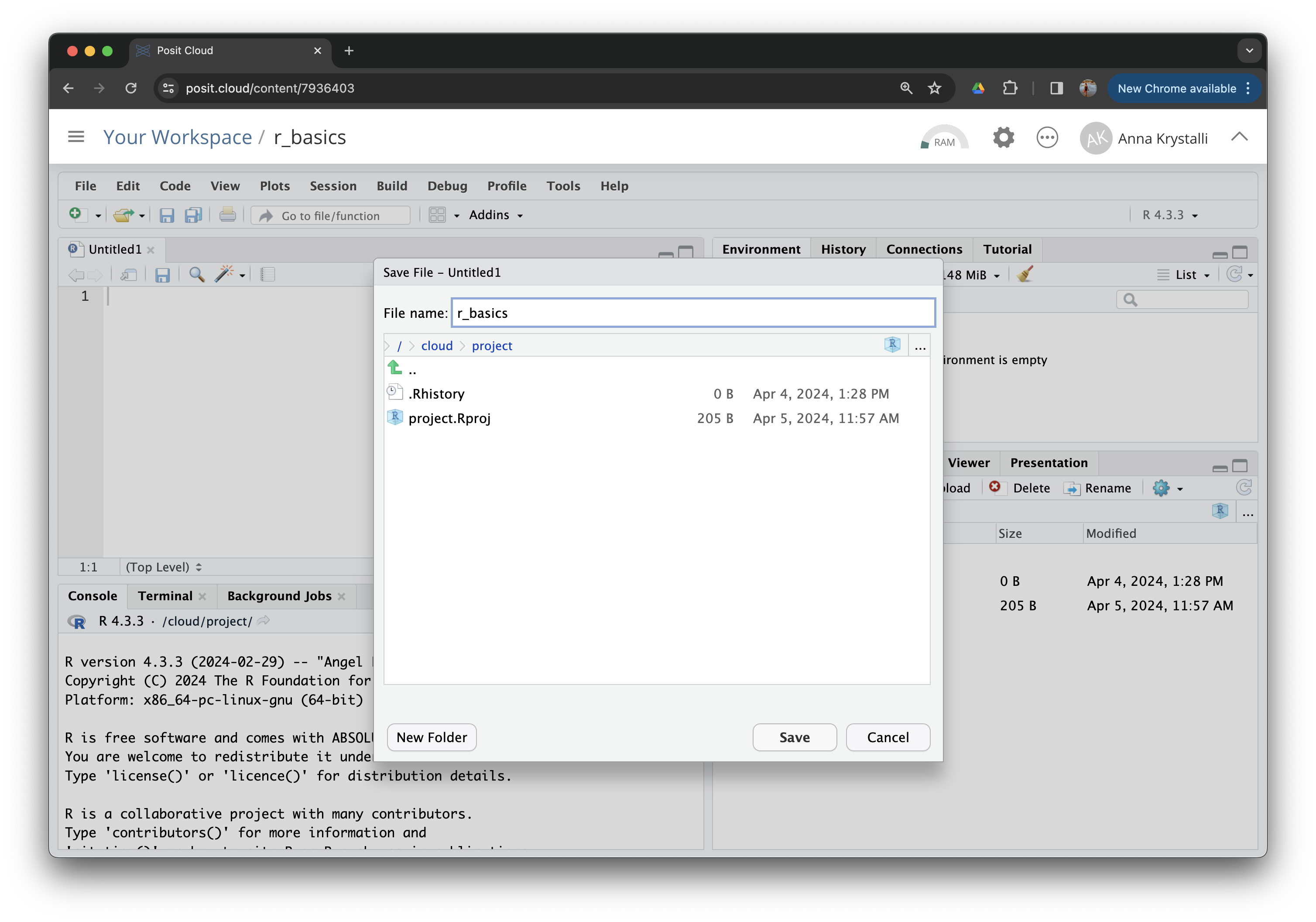

Click on File > New File > R Script. Click on the save icon or (like any other file) using keyboard shortcut CTRL / CMD + S

RStudio allows you to execute commands directly from the script editor by using the Ctrl + Enter shortcut (on Macs, Cmd + Return will work, too).

When you execute commands from a script, the line of code in the script indicated by the cursor or any commands currently highlighted will be sent to the console. You can find other keyboard shortcuts in Tools > Keyboard Shortcuts Help or in the RStudio IDE cheatsheet.

When using R as a calculator, the order of operations is the same as you would have learned back in school.

From highest to lowest precedence:

(, )

^ or **

*

/

+

-

3 + 5 * 2[1] 13Use parentheses to group operations in order to force the order of evaluation if it differs from the default, or to make clear what you intend.

(3 + 5) * 2[1] 16Really small or large numbers get a scientific notation:

2/10000[1] 2e-04Which is shorthand for “multiplied by 10^XX”. So 2e-4 is shorthand for 2 * 10^(-4).

You can write numbers in scientific notation too:

5e3 # Note the lack of minus here[1] 5000R has many built in mathematical functions. To call a function, we can type its name, followed by open and closing parentheses. Anything we type inside the parentheses is called the function’s arguments:

sin(1) # trigonometry functions[1] 0.841471log(1) # natural logarithm[1] 0log10(10) # base-10 logarithm[1] 1exp(0.5) # e^(1/2)[1] 1.648721Don’t worry about trying to remember every function in R. You can look them up on Google, or if you can remember the start of the function’s name, you can take advantage of the tab completion in RStudio.

This is one advantage that RStudio has over R on its own, it has auto-completion abilities that allow you to more easily look up functions, their arguments, and the values that they take.

Typing a ? before the name of a function will open the help page for that function. As well as providing a detailed description of the function and how it works, scrolling to the bottom of the help page will usually show a collection of code examples which illustrate how to use it. We’ll go through an example later.

We can store values in variables using the assignment operator <-, like this:

x <- 1/40Notice that assignment does not print a value. Instead, we stored the value in something called a variable. x now contains the value 0.025. We can examine the value contained in any variable by printing it’s contents to the console:

x[1] 0.025If we look at the Environment tab, we will see that variable x now exists in the environment and can also preview its value. Our variable x can be used in place of its value in any calculation that expects a number:

log(x)[1] -3.688879Notice also that variables can be reassigned:

x <- 100

x[1] 100x used to contain the value 0.025 and now it has the value 100.

Expressions to create re-assigned variables can contain the initial value of the variable being assigned to:

x <- x + 1 #notice how RStudio updates its description of x on the top right tab

y <- x * 2Variable names can contain letters, numbers, underscores and periods. They cannot start with a number nor contain spaces at all.

Different people use different conventions for long variable names, these include

While I suggest you use snake_case, ultimately what you use is up to you, but be consistent.

Even more important is that variable names are descriptive enough of what they contain. So long and descriptive is better than shorter and cryptic.

We can also do comparison in R. These return TRUE or FALSE.

x <- 1x < 2 # less than[1] TRUEx <= 1 # less than or equal to[1] TRUEx > 0 # greater than[1] TRUEx >= -9 # greater than or equal to[1] TRUEx <- "apple"

x == "apple" # equality (note two equals signs, read as "is equal to")[1] TRUEx == "orange"[1] FALSEx != "orange" # inequality (read as "is not equal to")[1] TRUEA word of warning about comparing numbers: you should avoid using == to compare two numbers unless they are integers (a data type which can specifically represent only whole numbers).

This is because of the way that R stores floating point numbers (i.e. of data type "double").

To compare floating point numbers safely, you should use the all.equal function, which is designed to compare floating point numbers within a certain tolerance. _

x <- 1.02

all.equal(x, 1.02)[1] TRUE& and |

We can combine comparisons using the & and | operators:

& (AND)& is effectively translated as “and”. When using & ALL conditions must be met for the whole statement to evaluate to TRUE.

x <- 4

x > 5 & x < 10 [1] FALSEIn this case, because we are using the & operator, the result in FALSE because, although x is less than 10, it is not greater than 5. Both conditions must be met for the whole statement to evaluate to TRUE.

| (OR)| is translated as “or” and only a single condition needs to be met for the whole statement to evaluate to TRUE.

x > 5 | x < 10 [1] TRUEThis time, because we are using the | operator, the condition is met if either x > 5 or x < 10 is true. In our case, although x is not greater than 5, it is less than 10, so the statement to evaluates to TRUE.

Comments

You can add comments to your code by using a hash symbol

#. Any text on a line of code following#is ignored by R when it executes code.